Impact of Initial Levels of Trust in Automation on Urban Rail Transit Driving Tasks

-

摘要:

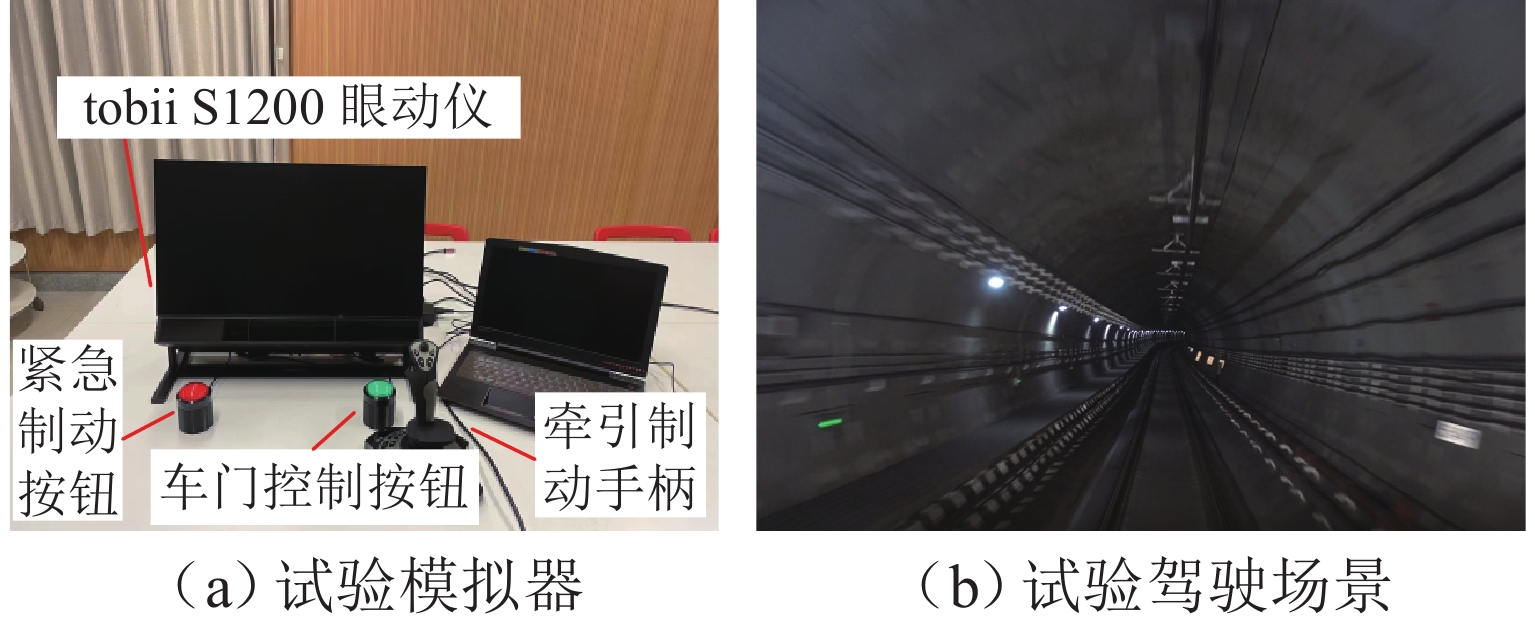

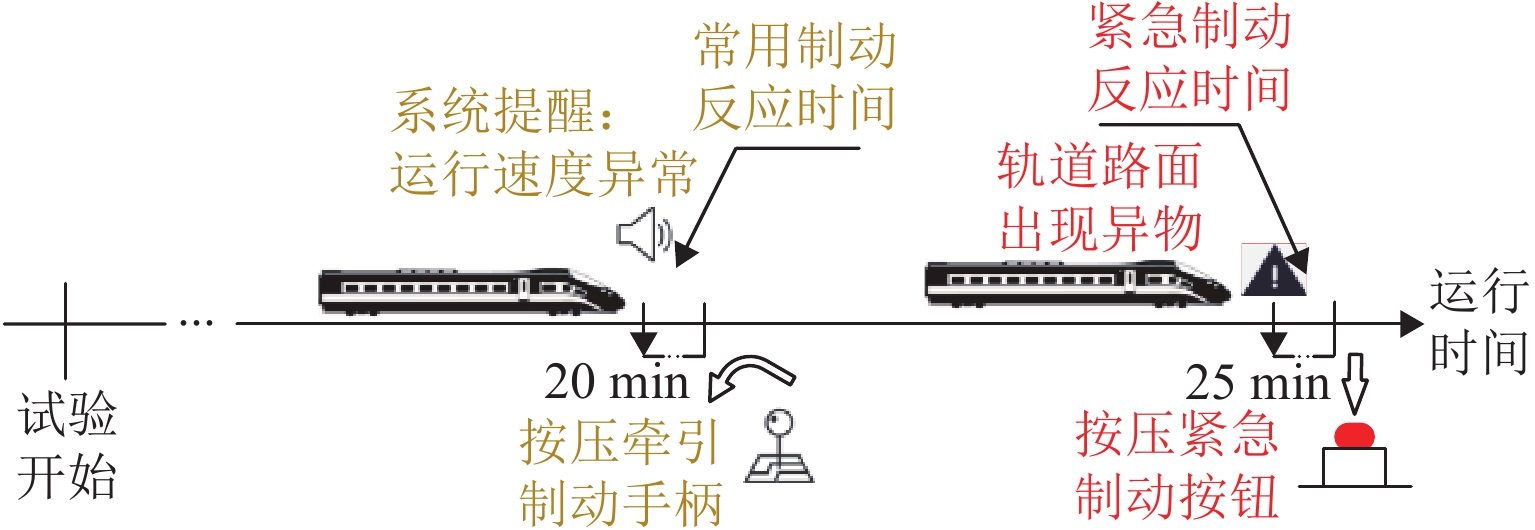

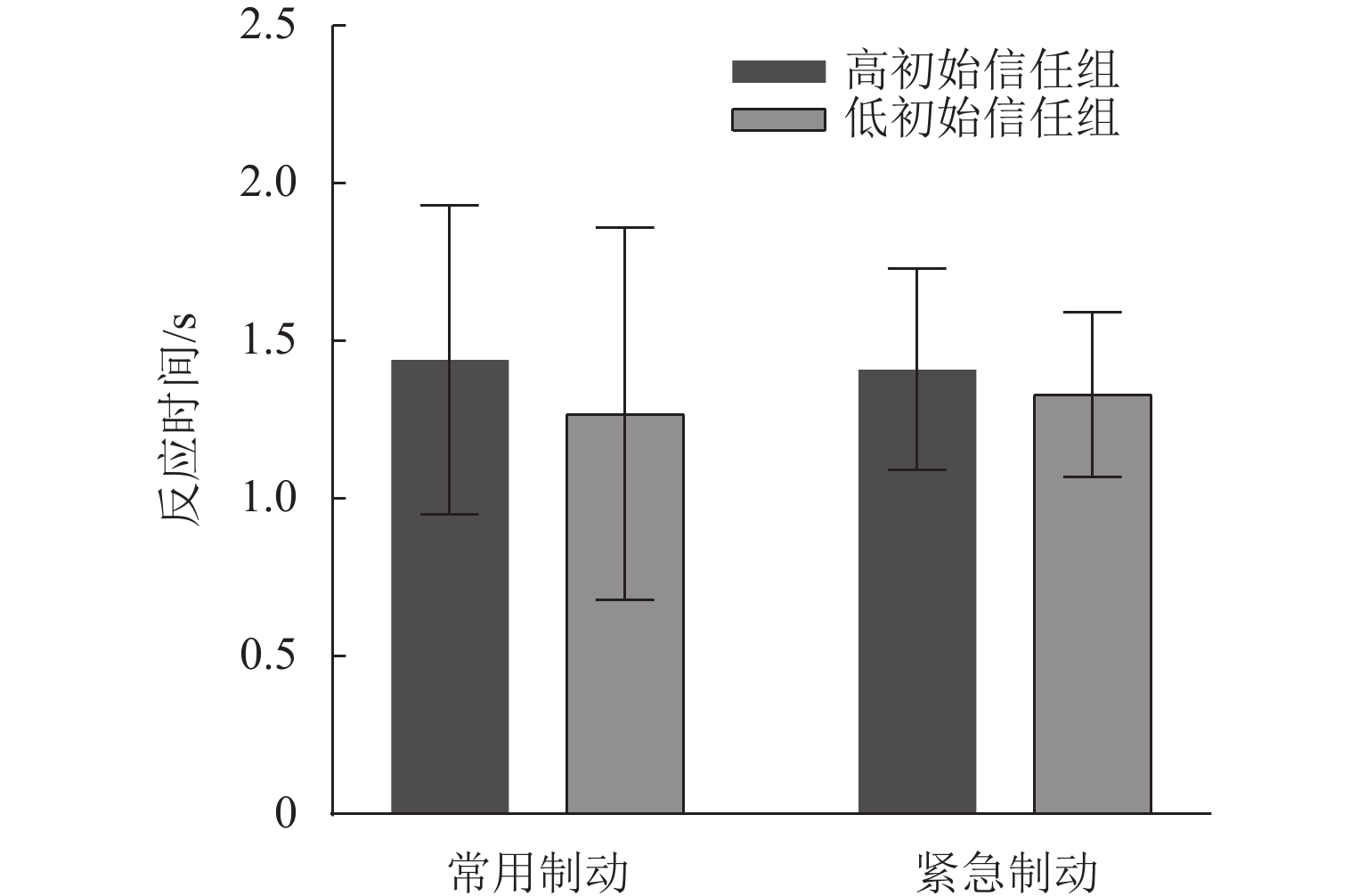

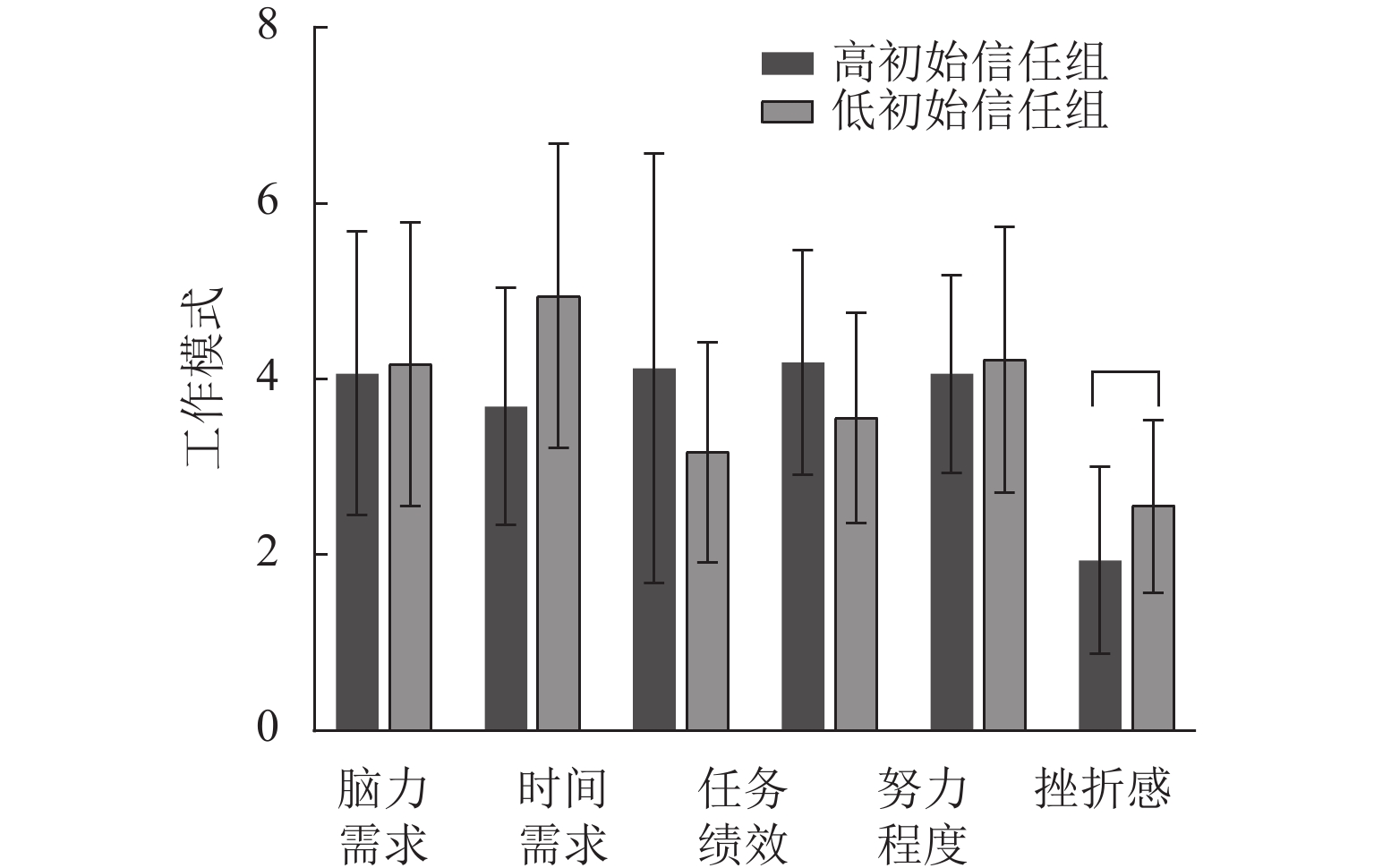

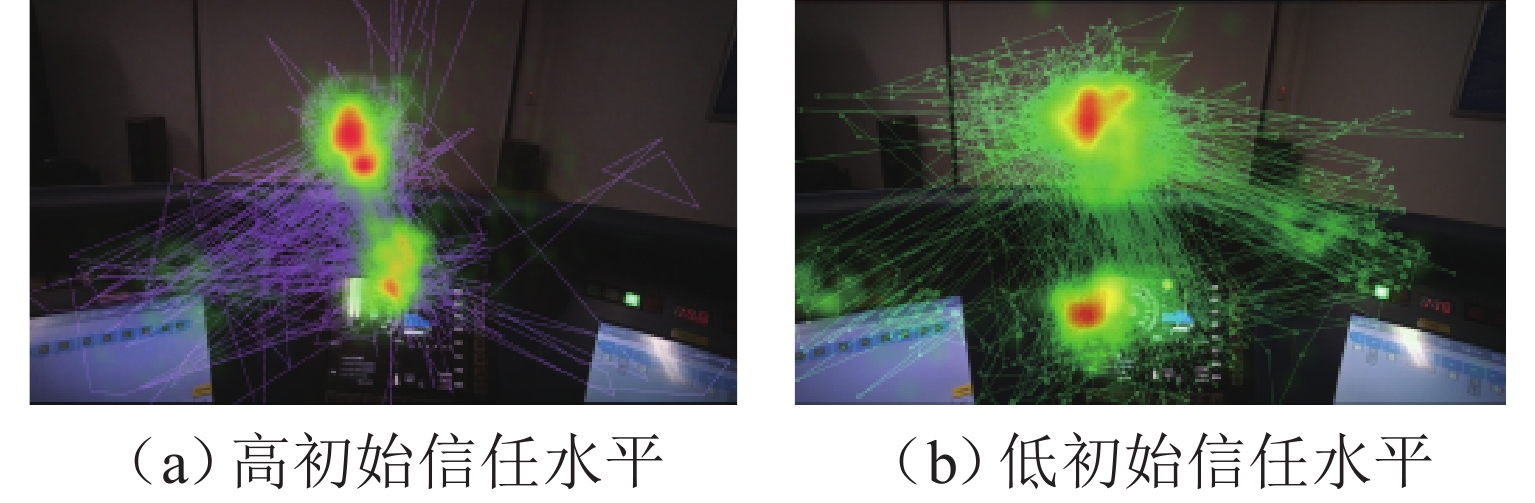

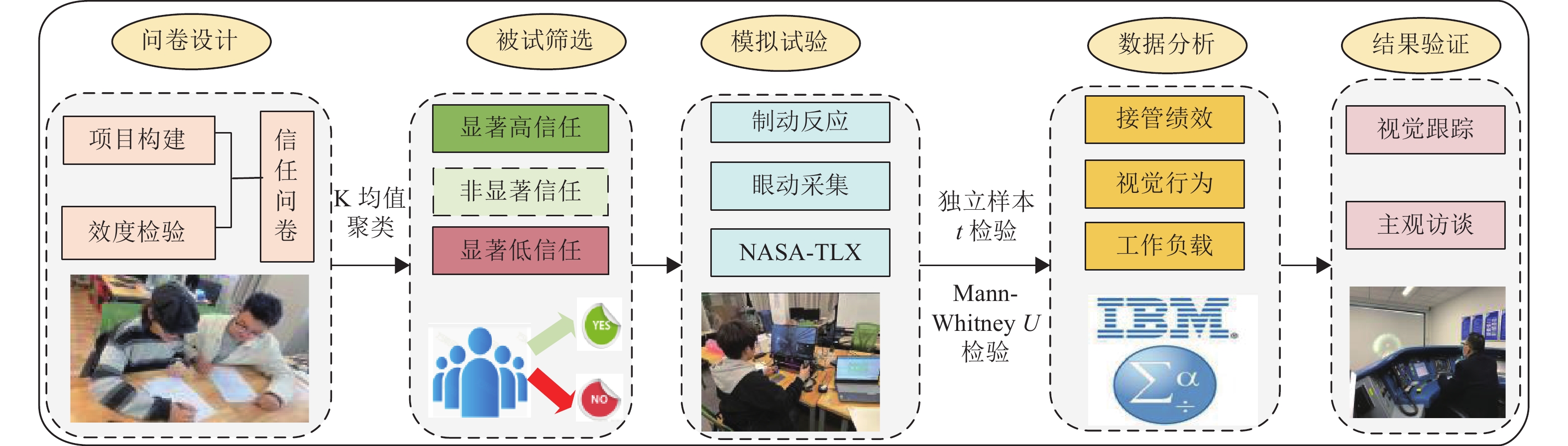

为明确自动化初始信任水平对城市轨道交通驾驶任务接管绩效、工作负载和视觉行为的影响,设计并验证自动化初始信任问卷,使用问卷筛选显著初始信任水平被试进行模拟驾驶试验;通过记录常用制动和紧急制动时间反应接管绩效,使用NASA-TLX (national aeronautics and space administration task load index)问卷计算工作负载,并分别采集轨道路面和驾驶界面2个区域的扫视次数、总注视次数、注视时间和平均注视时间以分析视觉行为差异. 试验结果表明:不同初始信任水平的参与者接管绩效不存在显著差异;高初始信任水平参与者相比低信任水平参与者整体工作负载低21.39%,身体负荷低34.24%和挫折程度低31.96%;初始信任水平显著影响视觉行为,低信任参与者趋向于活跃的视觉搜索行为,轨道路面的注视次数、轨道路面和驾驶界面的扫视次数分别高出28.14%、41.78%和42.91%;而高信任参与者趋向于固定的视觉凝视行为,轨道路面的平均注视时间高出40.74%. 研究可为城市轨道交通驾驶安全干预提供理论参考和实践依据.

Abstract:In order to ascertain the impact of the initial levels of trust in automation on takeover performance, workload, and visual behavior in urban rail transit driving tasks, a questionnaire assessing initial trust in automation was designed and validated. The questionnaire was used to screen participants with significantly different initial levels of trust for driving simulation tests. Takeover performance was evaluated by recording the response time of both routine and emergency braking. Workload was assessed by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Task Load Index (NASA-TLX) questionnaire. Additionally, data on visual behavior differences were analyzed by capturing saccade counts, total fixation counts, fixation durations, and mean fixation durations in two distinct areas separately: the rail surface and the driving interface. The results indicate that participants with different initial levels of trust show no significant difference in takeover performance. A 21.39% reduction in overall workload, a 34.24% reduction in physical demand, and a 31.96% reduction in frustration are observed among participants with high initial levels of trust compared with those with low levels of trust. The initial level of trust significantly influences visual behavior. Low-trust participants tend to exhibit active visual search behaviors, who demonstrate 28.14% more fixation counts on the rail surface, 41.78% more saccade counts to the road surface, and 42.91% more saccade counts to the driving interface. Meanwhile, high-trust participants tend to display fixed visual gaze behaviors, with a 40.74% longer mean fixation duration on the rail surface. The findings of this study offer theoretical guidance and practical implications for enhancing driving safety interventions in urban rail transit.

-

Key words:

- urban transportation /

- autonomous driving /

- trust in automation /

- takeover performance /

- workload /

- visual behavior

-

表 1 自动化初始信任评估问卷项目

Table 1. Initial trust in automation assessment questionnaire items

编号 量表选项 参考文献 1 我感觉城市轨道交通自动驾驶系统是可靠的 文献[19] 2 与手动驾驶相比,自动驾驶系统能为我提供更高的安全性 文献[19] 3* 我宁愿保持对车辆的手动控制,也不愿每次都将其委托给自动驾驶系统 文献[19] 4 我相信自动驾驶系统的反馈决策 文献[20] 5 我相信自动驾驶系统能够管理复杂的驾驶情况. 例如即使是运行状况非常复杂,我也会把驾驶任务交给自动驾驶 文献[21] 6 如果天气条件恶劣(例如,雾,眩光,下雨),我仍然会将驾驶任务委托给自动驾驶系统 文献[19] 7 自动驾驶系统可以帮助我降低警觉性不高和注意力不集中产生的错误,有了自动驾驶系统,我不需要完全的全神贯注 文献[22] 8 如果单调驾驶任务让我感觉很无聊,我宁愿把它委托给自动化系统,也不愿意自己手动驾驶 文献[23] 9 即使轮班制让我产生了困倦,有了自动化,我仍然可以放心进行驾驶任务 文献[24] 注:“*”表示结果分数反向转换. 表 2 初始信任水平分类结果

Table 2. Classification results of initial levels of trust

组别 样本量/名 得分范围 聚类中心 标准差 显著高信任 16 46~37 39.38 2.31 非显著信任 26 36~31 33.35 1.32 显著低信任 18 30~20 27.83 2.83 表 3 视觉行为比较结果

Table 3. Comparison results of visual behavior

兴趣区 视觉行为指标 高初始信任组 低初始信任组 t p 均值 标准差 均值 标准差 前方轨道路面 扫视次数/次 184.25 97.604 261.29 96.36 −2.281 0.030 总注视时间/s 637.36 196.88 604.15 124.84 0.582 0.565 总注视次数/次 1788.56 576.01 2291.88 395.41 −2.942 0.006 平均注视时间/(s·次−1) 0.38 0.17 0.27 0.06 2.472 0.019 操作界面 扫视次数/次 154.69 89.43 221.12 90.39 −2.121 0.042 总注视时间/s 152.68 86.14 163.22 72.23 −0.382 0.705 总注视次数/次 564.75 255.60 725.18 280.83 −1.713 0.097 平均注视时间/(s·次−1) 0.26 0.08 0.22 0.05 1.465 0.153 -

[1] 付世亮. 城市轨道交通车辆系统安全完整性等级分析[J]. 城市轨道交通研究, 2019, 22(10): 70-74.FU Shiliang. Safety integrity level analysis of urban guided transport vehicle system[J]. Urban Mass Transit, 2019, 22(10): 70-74. [2] 徐田坤. 城市轨道交通网络运营安全风险评估理论与方法研究[D]. 北京: 北京交通大学, 2012. [3] 向泽锐, 支锦亦, 李然, 等. 我国城市轨道列车工业设计研究综述[J]. 西南交通大学学报, 2021, 56(6): 1319-1328.XIANG Zerui, ZHI Jinyi, LI Ran, et al. Review on industrial design of urban rail vehicles in China[J]. Journal of Southwest Jiaotong University, 2021, 56(6): 1319-1328. [4] SINGH P, DULEBENETS M A, PASHA J, et al. Deployment of autonomous trains in rail transportation: current trends and existing challenges[J]. IEEE Access, 2021, 9: 91427-91461. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3091550 [5] WANG A B, GUO B Y, DU H, et al. Impact of automation at different cognitive stages on high-speed train driving performance[J]. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2022, 23(12): 24599-24608. doi: 10.1109/TITS.2022.3211709 [6] LEES T, CHALMERS T, BURTON D, et al. Electroencephalography as a predictor of self-report fatigue/sleepiness during monotonous driving in train drivers[J]. Physiological Measurement, 2018, 39(10): 105012.1-105012.13. [7] CHIOU E K, LEE J D. Trusting automation: designing for responsivity and resilience[J]. Human Factors, 2023, 65(1): 137-165. doi: 10.1177/00187208211009995 [8] LEE J D, SEE K A. Trust in automation: designing for appropriate reliance[J]. Human Factors, 2004, 46(1): 50-80. doi: 10.1518/hfes.46.1.50.30392 [9] ZHANG T R, TAO D, QU X D, et al. The roles of initial trust and perceived risk in public’s acceptance of automated vehicles[J]. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2019, 98: 207-220. doi: 10.1016/j.trc.2018.11.018 [10] KARPINSKY N D, CHANCEY E T, PALMER D B, et al. Automation trust and attention allocation in multitasking workspace[J]. Applied Ergonomics, 2018, 70: 194-201. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2018.03.008 [11] PAN H Y, XU K, QIN Y, et al. How does drivers’ trust in vehicle automation affect non-driving-related task engagement, vigilance, and initiative takeover performance after experiencing system failure[J]. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2023, 98: 73-90. doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2023.09.001 [12] 王新野, 李苑, 常明, 等. 自动化信任和依赖对航空安全的危害及其改进[J]. 心理科学进展, 2017, 25(9): 1614-1622. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2017.01614WANG Xinye, LI Yuan, CHANG Ming, et al. The detriments and improvement of automation trust and dependence to aviation safety[J]. Advances in Psychological Science, 2017, 25(9): 1614-1622. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2017.01614 [13] SKRAANING G, JAMIESON G A. Human performance benefits of the automation transparency design principle[J]. Human Factors, 2021, 63(3): 379-401. doi: 10.1177/0018720819887252 [14] SEBOK A, WICKENS C D. Implementing lumberjacks and black swans into model-based tools to support human–automation interaction[J]. Human Factors, 2017, 59(2): 189-203. doi: 10.1177/0018720816665201 [15] KÖRBER M, BASELER E, BENGLER K. Introduction matters: manipulating trust in automation and reliance in automated driving[J]. Applied Ergonomics, 2018, 66: 18-31. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2017.07.006 [16] DU Y, ZHI J Y, HE S J. Impact of experience on visual behavior and driving performance of high-speed train drivers[J]. Scientific Reports, 2022, 12: 5956.1-5956.10. [17] MANCHON J B, BUENO M, NAVARRO J. How the initial level of trust in automated driving impacts drivers’ behaviour and early trust construction[J]. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2022, 86: 281-295. doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2022.02.006 [18] KOHN S C, DE VISSER E J, WIESE E, et al. Measurement of trust in automation: a narrative review and reference guide[J]. Frontiers in Psychology, 2021, 12: 604977.1-604977.23. [19] BRANDENBURGER N, NAUMANN A. On track: a series of research about the effects of increasing railway automation on the train driver[J]. IFAC-PapersOnLine, 2019, 52(19): 288-293. doi: 10.1016/j.ifacol.2019.12.115 [20] O’CASS A, CARLSON J. An e-retailing assessment of perceived website-service innovativeness: implications for website quality evaluations, trust, loyalty and word of mouth[J]. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 2012, 20(1): 28-36. doi: 10.1016/j.ausmj.2011.10.012 [21] POWELL J P, FRASZCZYK A, CHEONG C N, et al. Potential benefits and obstacles of implementing driverless train operation on the Tyne and wear metro: a simulation exercise[J]. Urban Rail Transit, 2016, 2(3): 114-127. [22] RYAN B, WILSON J R, SHARPLES S, et al. Developing a rail ergonomics questionnaire (REQUEST)[J]. Applied Ergonomics, 2009, 40(2): 216-229. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2008.04.006 [23] BRANDENBURGER N, NAUMANN A, JIPP M. Task-induced fatigue when implementing high grades of railway automation[J]. Cognition, Technology & Work, 2021, 23(2): 273-283. [24] COTRIM T, CARVALHAIS J, NETO C, et al. Determinants of sleepiness at work among railway control workers[J]. Applied Ergonomics, 2017, 58: 293-300. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2016.07.006 [25] NIU J W, GENG H, ZHANG Y J, et al. Relationship between automation trust and operator performance for the novice and expert in spacecraft rendezvous and docking (RVD)[J]. Applied Ergonomics, 2018, 71: 1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2018.03.014 [26] OLSSON N. A validation study comparing performance in a low-fidelity train-driving simulator with actual train driving performance[J]. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2023, 97: 109-122. doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2023.07.007 [27] NAWEED A, CHAPMAN J, VANDELANOTTE C, et al. ‘Just right’ job design: a conceptual framework for sustainable work in rail driving using the goldilocks work paradigm[J]. Applied Ergonomics, 2022, 105: 103806.1-103806.18. [28] BERGGREN N, EIMER M. Visual working memory load disrupts template-guided attentional selection during visual search[J]. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 2018, 30(12): 1902-1915. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_01324 [29] HERGETH S, LORENZ L, VILIMEK R, et al. Keep your scanners peeled[J]. Human Factors, 2016, 58(3): 509-519. doi: 10.1177/0018720815625744 [30] NATSOULAS T. The tunnel effect, Gibson’s perception theory, and reflective seeing[J]. Psychological Research, 1992, 54(3): 160-174. doi: 10.1007/BF00922095 [31] STAPEL J, GENTNER A, HAPPEE R. On-road trust and perceived risk in Level 2 automation[J]. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2022, 89: 355-370. doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2022.07.008 [32] HARTWICH F, WITZLACK C, BEGGIATO M, et al. The first impression counts – A combined driving simulator and test track study on the development of trust and acceptance of highly automated driving[J]. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2019, 65: 522-535. doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2018.05.012 [33] WANG Z T, LI M K, ZHANG Q D, et al. High-speed train drivers’ operation performance: key factors, models, and management implications[J]. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 2023, 97: 103482.1-103482.10. [34] MA S, ZHANG W, YANG Z, et al. Promote or inhibit: an inverted U-shaped effect of workload on driver takeover performance[J]. Traffic Injury Prevention, 2020, 21(7): 482-487. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2020.1804060 -

下载:

下载: